Revisiting the Grand Budapest Hotel: The World of Yesterday with Stefan Zweig and Wes Anderson

Conflict resolution is on many Europeans’ minds these days. May 9 was Victory Day, marking 69 years since the end of World War II. On August 1, it will have been 100 years since the eruption of World War I. Both events are being commemorated with appropriately dignified wreath-laying ceremonies and political speeches about the danger of forgetting. And yet there are still so many troubles today — in Ukraine, Egypt, Syria, the Congo, South Sudan. The world financial crisis, the Snowden affair, political upheaval – aided and abetted by the Internet – are reason for many people to hearken back to what might have been a simpler time.

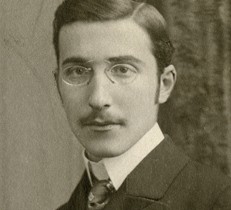

Stefan Zweig, Austrian Cultural Forum London, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 UK

The Austrian author Stefan Zweig grew up in a dignified, ordered society, in turn-of-the-20th-century Vienna. His melancholy but beautifully-written memoir Die Welt von Gestern (The World of Yesterday) is an agonizing description of how his carefree, richly intellectual life – the epitome of civilized European society – descended into despair. When Zweig was a boy, he tells us, people “knew their place.” Zweig means they knew where they came from; they belonged to tight-knit families and communities. Their sense of security, and their trust in the benevolence of their leaders, sustained most people through difficult times. Naturally some people had more and some considerably less, but in Zweig’s eyes society was unencumbered by the religious hatred and xenophobia that were later fomented by war. Though people weren’t free to break out of societal constraints in the modern sense, still Zweig argues that they treated one another with dignity and humanity.

But a perfect storm was brewing on the horizon. When a teenaged Serb named Gavrilo Princip assassinated Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria, European leaders failed to put the brakes on the runaway train of international tensions that ensued. War was cheered all ‘round; advances in technology made it easier to kill one’s new enemies at a distance, and in large numbers. Stefan Zweig’s tidy world was thrown into chaos.

After the drawn-out misery was finally over — treaties signed and culprits named — Europe started to get its bearings again. Hopefulness, and even exuberance, returned. Now was the time to press forward with a new vision of brotherhood and peace. There were many inventions which made life easier; there was a bit more leisure time and freedom to travel. A new emphasis on sport, and relaxed clothing standards, led to a new youth culture. The old Continental way of seeing the world, with its emphasis on the permanence of grace and beauty, were cast impatiently aside. Now was the time for youth to stride brashly forward; efficiency was king.

But a paltry 14 years after the Great War, the Continent was at it again.

Stefan Zweig was one of the world’s best-known authors in the early 1930’s. Despite his astonishing and well-tended connections to many of the great minds of the time, he suddenly found himself a homeless Jew, cut loose from conventionalities, his secure life a dream. When Nazis took over Austria, he fled to England. Nobody hated the Nazis more than he: in fact, he had been warning his readers about the dangers of complacency for years. Still, when England went to war with Germany, Zweig became an enemy in his adopted country. Stateless, humiliated, and unable to publish in his native tongue, this brilliant man, whose entire career was based on high ideals of brotherhood between peoples, fled once more, to Brazil. His story ends in unimaginable sorrow; he and his wife committed suicide together in 1942, one day after he had posted The World of Yesterday to a publisher.

Fassade des alten Jugendstil-Kaufhauses in Goerlitz, Lutzes Welt Blog.

Fassade des alten Jugendstil-Kaufhauses in Goerlitz, Lutzes Welt Blog.

Wes Anderson, the visionary American filmmaker, draws on Stefan Zweig’s writings as the basis of his hugely entertaining film The Grand Budapest Hotel. The movie’s popularity has spurred interest in Zweig’s works among English-speakers, who hadn’t fully embraced them earlier. Zweig’s English publisher Pushkin Press now features zippy bright covers on their reprints of his books. Pushkin has also recently published a movie tie-in for eggheads, The Society of the Crossed Keys, which features Zweig excerpts as selected by Anderson and curated by Zweig biographer George Prochnik. In a bizarre twist which he might have enjoyed, Stefan Zweig is given writer’s credit for 69 films in the International Movie Database, 72 years after his death.

Far from being a straight-on adaptation of a Zweig book, Anderson’s film merely touches on some Zweigian themes. The movie is set in a richly imagined Central European nation in the early 1930s (Anderson calls it “Nebelsbad, in the Alpine Sudetenwaltz,” which amused the German audience I saw the film with).Times are changing for Grand Hotels: society is in flux. The grand old rules of comportment, followed by everyone from Madame D. to the Concierge to the Lobby Boy, are starting to give way to brutishness. Like Zweig, Anderson shows us people living in well-ordered, gracious societies, jarred out of complacency when their comfortable bubbles burst and they find themselves buffeted by the winds of change.

Ein Wintertag im Palace Hotel St. Moritz, 1930

Of course Anderson’s film, though replete with fantastic, historically-based visual details and witty asides, taps into contemporary sensibilities. In the Zweig books there are no madcap dashes, no candy-colored uniforms, no old-school moustache-twirling villains or wise-cracking hustlers. Zweig’s tone tends toward the staid and erudite. And though he was certainly interested in people’s sexual proclivities (and a great friend of Freud), Zweig would never have put coarse language into his protagonists’ mouths.

Nothing remains forever, Anderson and Zweig remind us. Everything is fleeting. What was true in Vienna in 1910 is true today. Where there is upheaval, change will follow. It’s up to visionaries – political or artistic – to harness the energy of change, so it can be used for good instead of evil.